Obesity Clip Art Dont Use Any Computers or Tv for Kids Clipart

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Television viewing, computer use, obesity, and adiposity in United states of america preschool children

International Journal of Behavioral Diet and Physical Activity volume 4, Commodity number:44 (2007) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

There is express prove in preschool children linking media utilize, such as television/video viewing and computer use, to obesity and adiposity. Nosotros tested three hypotheses in preschool children: one) that watching > 2 hours of TV/videos daily is associated with obesity and adiposity, 2) that reckoner employ is associated with obesity and adiposity, and 3) that > 2 hours of media utilize daily is associated with obesity and adiposity.

Methods

Nosotros conducted a cross-sectional report using nationally representative information on children, aged 2–5 years from the National Health and Diet Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Our main outcome measures were 1) weight condition: normal versus overweight or at risk for overweight, and 2) adiposity: the sum of subscapular and triceps skinfolds (mm). Our chief exposures were Television receiver/video viewing (≤ two or > 2 hours/solar day), computer use (users versus non-users), and media use (≤ two or > 2 hours/24-hour interval). We used multivariate Poisson and linear regression analyses, adjusting for demographic covariates, to test the contained clan between TV/video viewing, figurer use, or overall media use and a child's weight status or adiposity.

Results

Watching > two hours/twenty-four hour period of Goggle box/videos was associated with being overweight or at risk for overweight (Prevalence ratio = ane.34, 95% CI [1.07, 1.66]; n =1340) and with higher skinfold thicknesses (β = 1.08, 95% CI [0.19, 1.96]; n = 1337). Calculator utilize > 0 hours/day was associated with higher skinfold thicknesses (β = 0.56, 95% CI [0.04, 1.07]; n = 1339). Media use had borderline significance with college skinfold thicknesses (β = 0.85, 95% CI [-0.04, ane.75], P=0.06; due north = 1334)

Conclusion

Watching > 2 hours/solar day of TV/videos in U.s. preschool-age children was associated with a college risk of being overweight or at risk for overweight and college adiposity–findings in support of national guidelines to limit preschool children'southward media use. Computer use was also related to college adiposity in preschool children, but not weight condition. Intervention studies to limit preschool children's media use are warranted.

Background

The epidemic of childhood obesity is a major public health problem in the US, where in 2003–2004, 26.2% of children aged two–5 years, 37.2% of children anile 6–11 years, and 34.3% of adolescents 12–xix years were at risk for overweight or overweight [i]. Some large epidemiological studies and one recent meta-analysis take found positive associations between idiot box viewing and childhood obesity [2–4]. Previous intervention studies in schoolhouse-age children have supported television and video viewing as causes of childhood obesity [5, vi]. In response to the growing problem of childhood obesity and other health issues associated with television viewing, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has issued national guidelines for parents to limit their children's total media time (with amusement media) to no more than 1 to two hours of quality programming per twenty-four hour period for children 2 years of historic period and older [seven–nine].

Television viewing is the nigh popular form of media use amidst young children [ten]. Some studies have linked television viewing to excess weight proceeds in preschool children [xi–xiii]. All the same, these studies had limitations. Outset, they measured boob tube/video viewing but not other forms of media such equally computer utilise. Moreover, some did not specifically test the AAP's ii-hour/twenty-four hour period cut-off with regard to media time and weight condition [11, 12], had samples limited to a specific age or geographic areas [11, 12], reported race/ethnicity as white or not white [13], or related television/video viewing to BMI but non other forms of adiposity [11–13]. While BMI is the recommended method for population-based screening of children for obesity, it was a poor predictor of body fat for individual children [14]. Other measures, such as skinfold thicknesses, were highly correlated with adiposity, [15] lipids [sixteen], and insulin [16] in children, and thus may provide additional useful data [17].

The AAP recommendation is not specific to television, but instead was written in terms of overall media use or what some phone call "screen time." At the time the initial recommendations were established, computer use amid preschoolers was very limited. That has now inverse. Estimator usage is chop-chop gaining in popularity among toddlers and preschool children. A series of Kaiser Family unit Foundation studies reported that 4–27% of children less than half dozen years of historic period used a computer on the assessment day for an average of most 1 hour [10, xviii, 19]. Like goggle box viewing, computer use may lead to decreased time spent existence physically active, which may predispose to excess weight gain. Notwithstanding to our cognition, the relationship betwixt computer use and weight status in United states of america preschool children has not been previously described.

The AAP's recommendation to limit media fourth dimension is a national 1, which underscores the importance for testing information technology on a nationally representative sample of preschool children, aged 2–5 years. Moreover, considering television viewing and obesity differ by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status [12, thirteen], it is likewise important to examine this relationship using nationally representative data to ensure adequate numbers of minority and depression-income subjects of differing urbanization types and regions of the country.

The main objective of this report was to test three hypotheses using nationally representative data on subjects aged 2–5 years from the National Health and Diet Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002: i) whether watching greater than two hours of television daily is independently associated with obesity (overweight or at risk for overweight) or adiposity (the sum of subscapular and triceps skinfolds), 2) whether computer use is independently associated with obesity or adiposity, and three) whether overall media use (tv/video viewing plus calculator use) greater than 2 hours daily is independently associated with obesity or adiposity, on a population level. We analyzed television viewing and computer use together because the AAP recommendation refers to media time and therefore encompasses both of these types of media utilize. Nosotros also analyzed them separately because the human relationship betwixt television set viewing and obesity is well studied, while the relationship between computer employ and obesity is not. For example, television use and its relationship to obesity is probable mediated past a number of factors such as 1) deportation of concrete activeness, 2) advertisements which encourage selection and consumption of low-nutrient, loftier caloric foods, and 3) increased dietary intake or snacking. In contrast, information technology is currently unknown whether reckoner use in preschoolers is associated with weight status.

Methods

Data source

The NHANES is a series of cross-sectional surveys conducted past the Centers for Illness Control and Prevention (CDC), which serves as one of the key measures for Good for you People 2010 [20]. We used NHANES 1999–2002, the latest, fully released version of NHANES, to obtain a nationally representative sample of the U.s.a. not-institutionalized civilian population through its complex, stratified, multistage, probability cluster sampling pattern. Most subjects were interviewed in-person although a small sub-sample was interviewed over the telephone. For children less than 6 years of age, proxy interviews were conducted. NHANES methods have been reported in particular elsewhere [21]. This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Academy of Washington Human Subjects Partitioning.

Subjects

For this analysis, nosotros chose all children, anile two to 5 years (due north = 1809). Subjects with missing data were excluded from analyses and the corresponding sample size is given for each analysis.

Outcome variables

Height, weight, triceps skinfold thickness, and subscapular skinfold thickness were obtained using standardized techniques and equipment [22]. Body mass alphabetize (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided past the square of elevation (meters2) and their corresponding BMI percentiles were calculated from the CDC growth charts [23]. Triceps and subscapular skinfolds were summed into 1 measure to provide a more global index of adiposity. Children were also classified as underweight (< vth %) according to World Health Organization guidelines [24], or normal weight (≥ 5thursday and < 85thursday %), at adventure for overweight (≥ 85th and < 95thursday %), and overweight (> 95th %), according to guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [23]. For the purposes of the multivariate Poisson regression models, nosotros dichotomized children into 2 categories by weight status: 1) normal weight (≥ 5th and < 85th % for historic period and gender) and two) at risk for overweight or overweight (> 85thursday % for age and gender). Underweight children were excluded from the multivariate analyses (n = 66).

Main exposure

Television/video viewing was a categorical variable and was assessed similarly to previous reports from older releases of NHANES [2, 25], by the following in which "SP" refers to sample person: "About how many hours did (SP) sit and watch TV or videos yesterday? Would you lot say less than 1 hour, one 60 minutes, 2 hours, 3 hours, four hours, 5 hours or more, or none?" In order to test the AAP guidelines in the multivariate analyses, we dichotomized Television receiver/video viewing into two categories: ii hours or less/twenty-four hours and greater than 2 hours/day. Computer use was likewise a chiselled variable and similarly assessed using the following: "Almost how many hours did (SP) use a estimator or play estimator games yesterday? Would you say less than ane hr, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 5 hours or more, or none?" Because estimator use was expected to exist depression among preschoolers, nosotros also dichotomized the variable to 0 hours/day and greater than 0 hours/solar day to allocate children as not-users and users, respectively. Because we were interested in assessing preschoolers' media time, we combined the television/video viewing and reckoner use variables into one measure, henceforth termed media use. In combining the categorical variables, we took a bourgeois approach and classified those participants who reported less than one hour of television or estimator use as having none.

Covariates

We adjusted for several covariates that might confound the relationship between TV/video viewing or computer use and our outcomes of interest. Socioeconomic and demographic variables were reported as follows: 1) Gender, 2) Age as a continuous variable, 3) Race/ethnicity categorized as non-Hispanic white, not-Hispanic black, Mexican-American, and Other; and 4) Household income reported every bit the poverty to income ratio (PIR), which is the ratio of income to the family's appropriate poverty threshold as determined by the United states Census Bureau [26]. PIR values less than 1 are below the poverty threshold, which is adapted annually for inflation with the Consumer Price Index. PIR was provided by NHANES in the following six categories: < ane, ≥ one < two, ≥ 2 < 3, ≥ iii < four, ≥ iv < 5, and ≥ 5 PIR [21].

Statistical analyses

We used the Pearson chi-squared statistic to test for 1) differences in the proportions of demographic variables and main exposures of tv set/video viewing, computer utilize, or overall media use by weight condition; 2) differences in the proportions of television/video viewing, estimator employ, or overall media utilize past socio-demographic covariates; and 3) differences in proportions of telly/video viewing versus computer use. Nosotros used a serial of multivariate Poisson regression models to determine the independent association between TV/video viewing (n = 1340), computer use (n = 1340), or media use (n = 1337), and a child's weight status, adjusting for gender, historic period, race/ethnicity, and household income. Nosotros also used a similar series of multivariate linear regression models, decision-making for socio-demographic variables, to make up one's mind the independent association between TV/video viewing (n = 1337), computer utilize (n = 1339), or media employ (northward = 1334), and the measure of adiposity: the sum of subscapular and triceps skinfold thicknesses. Subjects with missing information were dropped from each of the bivariate and multivariate regression models. Demographic differences between dropped subjects and those included in the multivariate Poisson regression model were tested past the Pearson chi-squared statistic.

Stata version 9 was used for all analyses (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Survey estimation commands for complex survey data were used in the analyses taking into account weighted observations and the probability of selection, nonresponse, and post-stratification adjustments, to obtain representative estimates of United states of america children 2 to five years sometime. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all analyses. We present means and standard errors (ways +/- standard errors) unless otherwise indicated. Taylor series linearization was used to estimate standard errors.

Results

Average age was 3.five years +/- 0.03 years (SE) and 51.8% +/- 2.1% were female. Sample sizes with their corresponding estimates of percentages for gender, race/ethnicity, income, media utilise, television viewing, and computer use past overweight status are given in Table 1. An estimated (uncorrected) 22.0% +/- one.5% were overweight or at take chances for overweight. Both media use and television/video viewing were associated with weight status in the bivariate analyses.

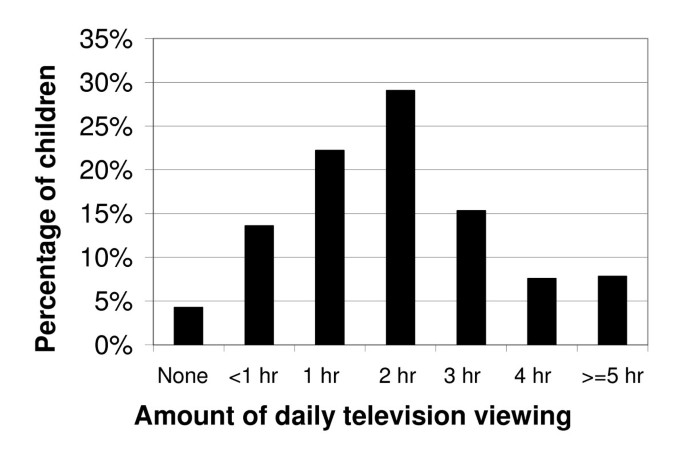

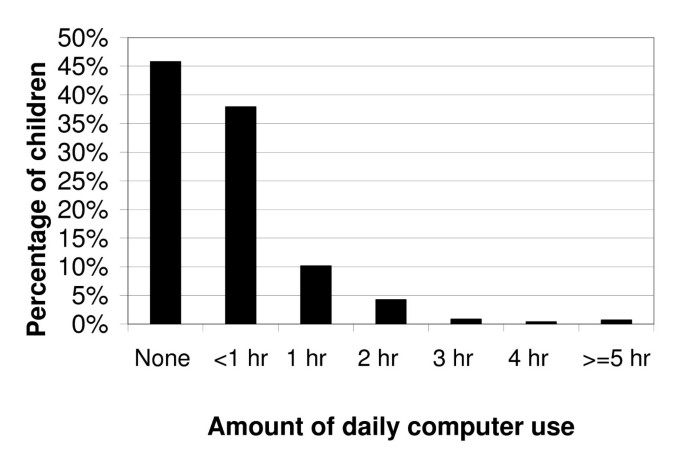

Tv set/video viewing was the more prevalent form of media use, compared to computer employ (Figures ane and 2). With regard to the AAP recommendations for limiting media use, xxx.eight% +/- two.0% of The states preschool children exceeded the guidelines past television viewing alone. About children watched between 1–3 hours of TV/videos on the cess solar day. Exceeding the AAP recommendations by television/video viewing alone was associated with higher age and poverty condition (P < 0.05, Table two). Not-Hispanic blacks and "Other" race preschoolers had the highest per centum who exceeded the recommendations when only because television/video viewing (P < 0.05, Table two). In dissimilarity, well-nigh preschool children used the figurer for less than i 60 minutes on the assessment day, or not at all (P < 0.05, Figure three). For case, while but four.3% +/- 1.ii% of children watched no TV/videos on the cess day, 45.8% +/- i.9% of children did not utilise a computer on the assessment day. Preschool children who were older or from families with higher incomes were more probable to have used a computer on the assessment day (P < 0.05, Table 3). Non-Hispanic black children were more likely to accept used a computer than their white peers, while Mexican-American children were less likely to have used a estimator on the assessment day (P < 0.05, Table 3). We found no significant differences by gender (P > 0.05, Tabular array 3). In combining telly/video viewing and computer use, we report that overall media use was prevalent among the ii–5 twelvemonth quondam participants and approximately 36.2% +/- 1.9% exceeded the AAP recommendations with this combined exposure (Effigy 3).

Percent of US children, anile 2–five years, by the corporeality of daily television/video viewing (n = 1796).

Percentage of US children, aged two–v years, past the amount of daily calculator use (n = 1799).

Percent of U.s. children, aged 2–five years, by the amount of daily media use (n = 1792).

In comparison boob tube/video viewing to computer use exposures (Table 4), higher television/video viewing was significantly associated with more estimator utilise (P < 0.0001), although computer use was more often than not modest for every level of idiot box/video exposure. Most preschool children, including those that watched 4 or more hours on the assessment day, spent ane-60 minutes or less on the computer. Reckoner use did not appear to displace television/video utilize since these exposures were positively correlated.

The hateful age of participants excluded from the multivariate Poisson regression models due to missing data (iii.ane years, 95% CI [3.0, three.3]) was slightly younger than the age of those with consummate data (three.5 years 95% CI [3.5, three.6]). However, participants did not differ with regard to gender, race/ethnicity, and poverty to income ratio (P > 0.05).

From the multivariate Poisson regression model, adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and income: compared to children who watched 2 hours or less of TV/videos on the assessment day, those who watched greater than two hours were more likely to be overweight or at take chances for overweight (Table 5, Prevalence ratio = 1.34, 95% CI [1.07, 1.66], P = 0.01). Moreover, only TV viewing, and not covariates such equally race/ethnicity or income, was significantly associated with weight status. From the multivariate linear regression model, watching more than ii hours of television on the assessment day was likewise associated with higher skinfold thicknesses (Tabular array 5, β = ane.08, 95% CI [0.xix, i.96], P = 0.02). Female person gender was also associated with higher skinfold thicknesses (Tabular array 4).

From the multivariate linear regression model, adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and income: computer apply ( > 0 hours on the assessment day) was associated with higher skinfold thicknesses (Table 6, β = 0.56, 95% CI [0.04, 1.07], P = 0.04). Female gender was also associated with higher skinfold thicknesses (Table 6), while computer use was not associated with weight status (P > 0.05).

From the multivariate linear regression model, adjusting for historic period, gender, race/ethnicity, and income: media employ in excess of ii hours on the assessment day had a deadline meaning association with increased skinfold thicknesses (Table 7, β = 0.85, 95% CI [-0.04, 1.75], P = 0.06). Female gender was also associated with higher skinfold thicknesses (Tabular array 7). Media use for more than than two hours on the assessment day was not associated with higher weight condition (P > 0.05). Nosotros were unable to analyze the above multivariate models stratified by race/ethnicity due to the lack of participants in more one primary sampling unit for sure covariates.

Discussion

In a large, population-based survey of children, anile 2–5 years, we study that a substantial proportion of preschoolers exceeded the AAP recommendations to limit media fourth dimension to less than 2 hours daily. This finding is consistent with previous studies in preschoolers [10, 12, 13]. Preschoolers had a higher prevalence and greater exposure to tv set/video viewing than computer utilise as previously reported [ten]. Importantly, we report that Goggle box/video viewing for more than two hours per 24-hour interval in this nationally representative sample of US preschoolers was independently associated with existence overweight or at risk for overweight and with higher adiposity as measured by skinfold thicknesses. These results update and aggrandize the findings of a previous large study on 3 twelvemonth old children that used older data from the early to mid 1990s [13] and highlights the importance of goggle box viewing to weight status and adiposity in early childhood.

In dissimilarity, we written report that computer apply among preschoolers is low, consistent with previous reports [ten, nineteen, 27, 28]. From the bivariate analyses, reckoner employ generally increased with increasing historic period and income. Additionally, compared to not-Hispanic white children, more not-Hispanic black children were reported to take used a estimator on the cess solar day while fewer Mexican American children did. These findings build upon a previous survey that reported similar demographic associations for 6 calendar month to 6 twelvemonth olds with regard to ever having used a estimator [28]. It is thought that admission to computers at schools [27] coupled with heavier computer use may assist explain why previous reports accept documented that African-American children used computers either more [28] or at the aforementioned level [19] as white children. Given preschooler'southward depression exposure to computer use, immature motor skills, and the relative lack of age-appropriate software, it was non surprising that preschooler'due south computer utilise was low, nor the lack of association with weight status. Surprisingly, any figurer apply ( > 0 hours per day) was independently associated with higher adiposity, as measured past the sum of triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses. The relationship betwixt computer use and adiposity warrants confirmation and further written report, particularly as the trend for increasing figurer use continues among preschool children as more software aimed at preschoolers becomes bachelor. Like to computer use, the blended measure of media utilise for more 2 hours on the assessment day had borderline association with higher adiposity, as measured past the sum of triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses (β = 0.85, 95% CI [-0.04, 1.75], P = 0.06), but non with weight status (P > 0.05).

This study has several limitations. Kickoff, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes drawing causal inferences. Nevertheless, given that the relationship between Telly/video viewing and backlog weight has been identified by intervention trials in schoolhouse-age children, information technology seems plausible that this relationship holds true to some extent in their younger peers. While Dennison and colleagues have previously reported that a preschool-based intervention tin reduce Idiot box/video viewing in 2–5 year old children, they were unable to show a departure in change in BMI between the intervention and controls [29]. This lack of change in BMI may exist due to the modest sample size of this trial–only 77 subjects had complete follow-up data as compared to 192 subjects in Robinson's intervention trial involving threerd and 4thursday grade students in which he showed the relationship between television set viewing and excess weight gain [v]. Larger, long-term, controlled intervention trials for preschool-age children are necessary to clarify this effect. Second, boob tube viewing and estimator use were obtained by single item question and parental study, which may limit their validity [xxx]. However, previous studies that have compared straight parental estimates of children'due south television viewing have reported meaning correlation with goggle box diaries [31] and showed no systematic bias [32]. Random mistake would likely bias our findings towards the null hypothesis. Third, the effect sizes of the television/video (rii = 0.042) or estimator (r2 = 0.037) multivariate models were modest, although they were consistent with those from a recent meta-analysis [4], and were not unexpected due to the cross-sectional design of the study. Moreover, since single item, parent recalls were used to assess the television/video and computer exposures, these subjective measures may contribute to the weak associations with adiposity in this written report and other studies as previously reviewed [30], rather than there being a true minor consequence size. Fourth other forms of media use such every bit video game panel playing were not assessed. Moreover, combining boob tube/video viewing with computer apply probable underestimated true media use since we took a conservative approach and classified those participants who reported less than ane hour of telly or computer utilize as having none. This approach may as well bias our findings for overall media use towards the cipher hypothesis, and help explain why we found only borderline association betwixt media use and adiposity and no association with weight condition. Finally, the survey provides no information on the content of media employ, and and so we cannot define which types of programs or advertisements are associated with higher weight condition and adiposity.

Decision

This report confirms that a substantial percent (most 36%) of US preschool children exceeded the AAP recommendation to limit media fourth dimension to 2 hours or less per day. The majority of media time was spent on television/video viewing rather than figurer utilize. Moreover, nearly 31% of preschool children exceeded the AAP recommendation by idiot box/video viewing alone. This report provides support using contempo, nationally representative data for the AAP'southward recommendation to limit television/video viewing with regard to obesity and adiposity in U.s. preschoolers. Intervention studies to preclude and treat obesity in preschool children by reducing Television set/video viewing are warranted. Further research is necessary to determine what mediates the relationship between Telly/video viewing and a kid's weight status. This written report is the offset to written report a relationship between figurer utilise among preschool children and higher adiposity. More studies are necessary to confirm and explore this relationship.

Abbreviations

- AAP:

-

American Academy of Pediatrics

- NHANES:

-

National Wellness and Nutrition Examination Survey

- CDC:

-

Centers for Illness Command and Prevention

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- PIR:

-

poverty to income ratio

- SE:

-

standard error

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

References

-

Ogden CL, Carroll Medico, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM: Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Jama. 2006, 295 (thirteen): 1549-1555. ten.1001/jama.295.xiii.1549.

-

Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Bartlett SJ, Cheskin LJ, Pratt M: Relationship of concrete activity and idiot box watching with body weight and level of fatness among children: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Jama. 1998, 279 (12): 938-942. 10.1001/jama.279.12.938.

-

Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH: Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996, 150 (four): 356-362.

-

Marshall SJ, Biddle SJ, Gorely T, Cameron N, Murdey I: Relationships between media use, body fatness and physical activity in children and youth: a meta-assay. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28 (10): 1238-1246. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802706.

-

Robinson TN: Reducing children'due south boob tube viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 1999, 282 (16): 1561-1567. x.1001/jama.282.16.1561.

-

Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Play a trick on MK, Laird N: Reducing obesity via a schoolhouse-based interdisciplinary intervention amongst youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999, 153 (4): 409-418.

-

Children, adolescents, and television. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Communications. Pediatrics. 1995, 96 ((4 Pt 1)): 786-787.

-

Barlow SE, Dietz WH: Obesity evaluation and treatment: Skilful Committee recommendations. The Maternal and Child Health Agency, Health Resource and Services Administration and the Section of Health and Human Services. Pediatrics. 1998, 102 (3): E29-10.1542/peds.102.3.e29.

-

Krebs NF, Jacobson MS: Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2003, 112 (2): 424-430. x.1542/peds.112.2.424.

-

Vandewater EA, Rideout VJ, Wartella EA, Huang X, Lee JH, Shim MS: Digital childhood: electronic media and technology utilise among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Pediatrics. 2007, 119 (v): e1006-1015. 10.1542/peds.2006-1804.

-

Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Thompson D, Greaves KA: BMI from 3–6 y of age is predicted past TV viewing and physical activity, non diet. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005, 29 (6): 557-564. x.1038/sj.ijo.0802969.

-

Dennison BA, Erb TA, Jenkins PL: Tv set viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk amid low-income preschool children. Pediatrics. 2002, 109 (6): 1028-1035. 10.1542/peds.109.vi.1028.

-

Lumeng JC, Rahnama Southward, Appugliese D, Kaciroti N, Bradley RH: Telly exposure and overweight risk in preschoolers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006, 160 (iv): 417-422. 10.1001/archpedi.160.four.417.

-

Ellis KJ, Abrams SA, Wong WW: Monitoring childhood obesity: assessment of the weight/meridian alphabetize. Am J Epidemiol. 1999, 150 (9): 939-946.

-

Steinberger J, Jacobs DR, Raatz Southward, Moran A, Hong CP, Sinaiko AR: Comparison of torso fatness measurements by BMI and skinfolds vs dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and their relation to cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005, 29 (11): 1346-1352. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803026.

-

Freedman DS, Serdula MK, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS: Relation of circumferences and skinfold thicknesses to lipid and insulin concentrations in children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Eye Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999, 69 (2): 308-317.

-

Pietrobelli A, Peroni DG, Faith MS: Pediatric body composition in clinical studies: which methods in which situations?. Acta diabetologica. 2003, 40 (Suppl one): S270-273. x.1007/s00592-003-0084-0.

-

Rideout VJ, Vandewater EA, Wartella EA: Zero to six: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddlers and preschoolers. 2003, Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family unit Foundation

-

Rideout VJ, Hamel East: The media family unit: Electronic media in the lives of infants, toddlers, preschoolers and their parents. 2006, Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family unit Foundation

-

Good for you People 2010. 2000, Washington, DC: US Authorities Printing Office, 2

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999-Current National Health and Nutrition Exam Survey (NHANES). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/almost/major/nhanes/currentnhanes.htm]

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Anthropometry Procedures Manual. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/almost/major/nhanes/current_nhanes_01_02.htm]

-

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL: 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat eleven. 2002, 1-190. 246

-

Physical condition: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Wellness Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995, 854: 1-452.

-

Crespo CJ, Smit East, Troiano RP, Bartlett SJ, Macera CA, Andersen RE: Television set watching, free energy intake, and obesity in US children: results from the third National Wellness and Diet Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001, 155 (3): 360-365.

-

US Demography Bureau. How the Census Bureau Measures Poverty. [http://www.census.gov/hhes/world wide web/poverty/povdef.html]

-

Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF, Brodie K: Executive summary: Kids & media @ the new millenium. 1999, Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation

-

Calvert SL, Rideout VJ, Woolard JL, Barr RF, Strouse G: Age, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Patterns in Early Computer Use: A National Survey. American Behavioral Scientist. 2005, 48 (five): 590-607. 10.1177/0002764204271508.

-

Dennison BA, Russo TJ, Burdick PA, Jenkins PL: An intervention to reduce television viewing by preschool children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004, 158 (ii): 170-176. x.1001/archpedi.158.2.170.

-

Bryant MJ, Lucove JC, Evenson KR, Marshall Southward: Measurement of idiot box viewing in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007, 8 (3): 197-209. x.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00295.x.

-

Anderson DR, Field DE, Collins PA, Lorch EP, Nathan JG: Estimates of young children's time with television: a methodological comparison of parent reports with fourth dimension-lapse video abode observation. Child development. 1985, 56 (5): 1345-1357. 10.2307/1130249.

-

Borzekowski DLG, Robinson TN: Viewing the viewers: Ten video cases of children's television viewing behaviors. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1999, 43 (four): 506-528.

Acknowledgements

We give thanks Tom Baranowski, PhD, for critically reviewing drafts of this manuscript. A portion of this enquiry projection was conducted by J.A.M. while a senior swain in the University of Washington Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program, which had no role in the study design, data assay or estimation, or manuscript preparation and submission. The views expressed in this commodity are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Robert Forest Johnson Foundation or the Academy of Washington. This piece of work is also a publication of the United States Section of Agronomics (USDA/ARS) Children'south Nutrition Inquiry Heart, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor Higher of Medicine, Houston, Texas, and had been funded in function with federal funds from the USDA/ARS under Cooperative Agreement No. 58-6250-6001. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reverberate the views or policies of the USDA, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement from the US government.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JAM participated in the study's conception and design; led the analysis and interpretation of data; and drafted the manuscript. FJZ participated in the blueprint, analysis, and interpretation of information and helped to draft the manuscript. DAC participated in the conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of data and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Cardinal Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/2.0), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendoza, J.A., Zimmerman, F.J. & Christakis, D.A. Television viewing, computer utilise, obesity, and adiposity in US preschool children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Human activity 4, 44 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-4-44

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-4-44

Keywords

- Preschool Kid

- Weight Status

- Telly Viewing

- Skinfold Thickness

- Multivariate Linear Regression Model

Source: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1479-5868-4-44

0 Response to "Obesity Clip Art Dont Use Any Computers or Tv for Kids Clipart"

Post a Comment